On December 19, 1880, Garrett killed Tom O’Folliard, a member of McCarty's gang, in a shootout on the outskirts of Fort Sumner. On December 23, the sheriff's posse killed Charlie Bowdre, and captured the Kid and his companions at Stinking Springs. Garrett transported the captives to Mesilla, New Mexico, for trial. Though he was convicted, the Kid managed to escape from the Lincoln County jail on April 28, 1881, after killing his guards. On July 14, 1881, Garrett visited Fort Sumner to question a friend of the Kid's about the Whereabouts of the outlaw. He learned the Kid was staying with a mutual friend, Pete Maxwell. Around midnight, Garrett went to Maxwell's house. The Kid was asleep in another part of the house, but woke up hungry in the middle of the night and entered Maxwell's bedroom, where Garrett was standing in the shadows. The Kid did not recognize the man standing in dark. Garrett shot him twice, the first shot hitting him above the heart, although the second one missed and struck the mantle behind him. (Some historians have questioned Garrett's account of the shooting, alleging the incident happened differently. They claim Garrett went into Paulita Maxwell's room and tied her up. The Kid walked into her room, and Garrett ambushed him with a single blast from his rifle.

Billy the Kid's Grave

There has been much dispute over the details of the Kid's death that night. The way Garrett allegedly killed McCarty without warning eventually sullied the lawman's reputation. Garrett claimed Billy the Kid had entered the room armed with a pistol, but no gun was found on his body. Other accounts claim he entered carrying a kitchen knife, but no hard evidence supported this. Garrett's reputation was also hurt by popular stories that he and Billy had once been friends, and that the shooting was a kind of betrayal, but historians have found no evidence of such a friendship. Still, at the time, the shooting solidified Garrett's fame as a lawman and gunman, and led to numerous appointments to law enforcement positions, as well as requests that he pursue outlaws in other parts of New Mexico.

His law enforcement career never achieved any great success following the Lincoln County War, and he mostly used that era in his life as his stepping-stone to higher positions. After finishing out his term as sheriff, Garrett became a rancher and released a book in 1882 titled, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, which was a first-hand account about his experiences with McCarty, which helped raise the Kid to the level of historical figure, was in large part ghost written by his friend Ash Upson. Garrett lost the next election for Lincoln County sheriff and was never paid the $500 reward for McCarty's capture, since he had killed him. In 1882, he ran for the position of Sheriff of Grant County, but was defeated. In 1884, he lost an election for the New Mexico State Senate. Later that year, he left New Mexico and helped found and captain a company of Texas Rangers.

On December 20, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt, who became a personal friend of Garrett, appointed him customs collector in El Paso, Texas. Garrett served for five years. He then retired to his ranch in New Mexico but was suffering financial difficulties. He owed a large amount in taxes and was found liable for an unpaid loan he had cosigned for a friend. Garrett borrowed heavily to make these payments and started drinking and gambling. By this time, questions surrounding the manner in which Garrett had killed Billy the Kid and his general demeanor had led to his becoming quite unpopular. He no longer had any local political support, his support from President Roosevelt had been withdrawn, and he had few friends with power.

On February 29, 1908, Garrett and Carl Adamson, who was in the process of talks with Garrett to purchase land, rode together, heading from Las Cruces. Jesse Brazel showed up on horseback along the way. Garrett and Brazel began to argue about the goats grazing on Garrett's land. Garrett is alleged to have leaned forward to pick up a shotgun on the floorboard. Brazel shot him once in the stomach, and then once more in the head as Garrett fell from the wagon. Brazel and Adamson left the body by the side of the road and returned to Las Cruces, alerting Sheriff Felipe Lucero of the killing.

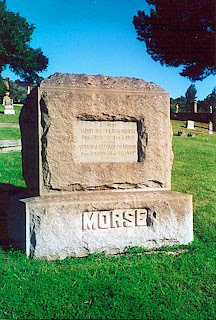

There has occasionally been disagreement about the identity of Pat Garrett's killer. Today, most historians believe Jesse Brazel, who confessed to the shooting and was tried for first degree murder, did in fact commit the crime. Brazel claimed self defense, claiming Garrett was armed with a shotgun and was threatening him. Adamson backed up Brazel's story. The jury took less than a half-hour to return a not guilty verdict. Cox hosted a barbecue in celebration of the verdict. To date, the common belief is the death happened as Brazel said it did. Garrett was known to have carried a double-barreled shotgun when he traveled, and he had a fiery temper. Garrett could have reacted violently during his argument with Brazel. Garrett's body was too tall for any finished coffins available, so a special one had to be shipped in from El Paso. His funeral service was held March 5, 1908, and he was laid to rest at the Masonic Cemetery in Las Cruces, next to his daughter, Ida.

Garrett family plot at the Masonic Cemetery in Las Cruces

.jpg)